MACK recently released their third book with Dutch photographer Bertien van Manen. When I first heard the book's title, Moonshine, my thoughts were flooded with images of the hillbilly stereotype. I thought about the title for a while, but spent more time exploring why my first thoughts were negative and what role that plays in my own understanding.

As an Appalachian, I am quick to react to any perceived negative stereotype. I spend a good deal of time thinking and writing about and making work in Appalachia. It's also important for me to think about how to address these issues in ways that might further more of a conversation rather than shaking my fist. I feel that this in an important part in the evolution of the conversation about looking at Appalachia.

Rather than rant about the book or its title before literally ever seeing it, I decided to wait until I could spend some time with, read the photographer's notes, take in the pictures, and try to sort out how I feel about the work and what that means to me as both an Appalachian and a photographer. Admittedly, the first paragraph is hard choke down:

"Moonshine is the illegally produced, homemade whisky, which has been distilled in the American Appalachians for centuries, by light of the moon. Tucked away at the back of every refrigerator in Kentucky, Tennessee or West Virginia, you might find two or three large apple-juice bottles filled to the brim with what looks like water. The clearer the liquid, the stronger the alcohol content. There's nothing more hallucinating than Moonshine and reefers on a hot, sultry summer evening out on the porch, in the silence of the mountains, with only the zoom of the bug zapper or the twang of the hillbillies' voices rising as they grow merry."

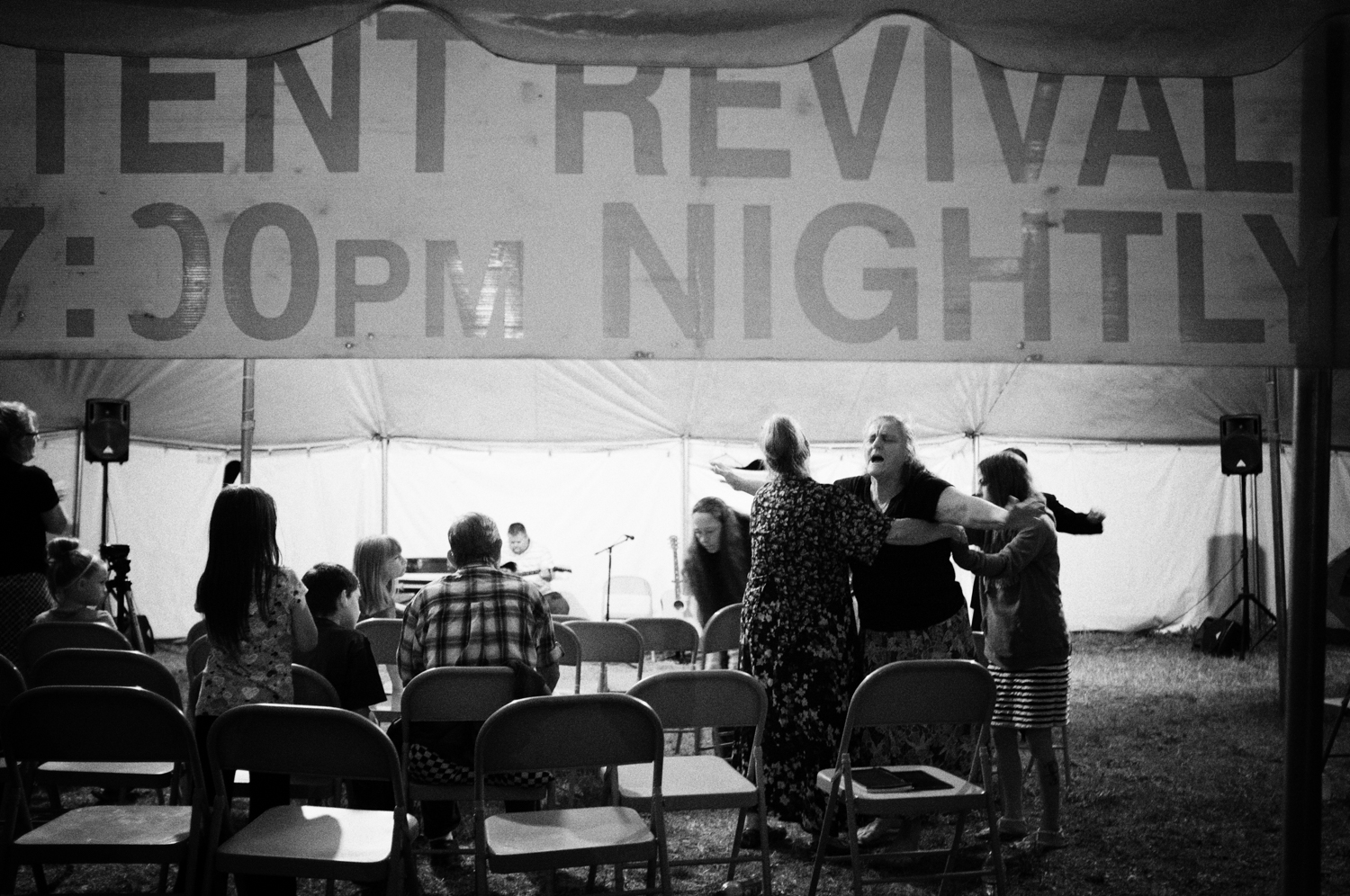

See what I mean? For those of you seething at this point, I might point out the rather beautiful title I would've chosen for this body of work, in the very first sentence - by the light of the moon. But this is not my book and this not my work. This paragraph alone is filled with problematic language that recalls dozens of others images that perpetuate the visual Appalachian stereotype. Once can likely argue that this book offers no absence of them, however I am smitten by the power they hold for me. Yes, smitten. Guns, trailers, dogs, porches, knives, camouflage, and Jesus are found in these pages to be sure, but I also found family, beauty, grace, and childlike wonder. Wonder.

The first pass I made through the photographs, I wished I hadn't read the introductory text. For me, there is a clear separation between what is written - the literal - and what is represented in the pictures - far more subjective. Pictures mean different things to different people. We all have our own imprinting and bring a host of learned looking filters to how we see the world and all that's in it. I'm only writing about my own, which is all I'm qualified to do. For the span of time these photographs cover, I wanted more in the text. Instead, we are offered two pages with a few paragraphs noting the highlights of of each of van Manen's trips. With that said, this is a photobook about Appalachia not a novel. In fact, it's a photobook about a family in Appalachia, rather than about Appalachia. Despite the title, Moonshine is a fine photobook, beautifully printed, rich in the sort of access not often seen.

Not wanting to start and end this conversation in my head, I emailed Bertien van Manen and she graciously agreed to answer some questions about the work and her career.

Roger May: What connection led you to begin making work in Appalachia in 1985?

Bertien van Manen: Being raised in a coal-mining area in the south of Holland, I have a fascination for coal-mining and coal-miners. I went taking pictures in the coal mining area of west Yorkshire, in the UK, where I met Vic Allen, a professor in mining, who told me that he heard that in the Appalachian mountains women were working as coal-miners.

RM: Photographing people and the region of Appalachia can often yield unfair criticism, particularly in light of the flow of images that have been used to stereotype the region. Of course, this isn’t unique to Appalachia. People are stereotyped all over the world. How conscious were you of how the work might be interpreted and how much of that, if any, plays a role in how you make work?

BVM: I was very well aware of this, especially after I saw a photobook of a photographer of the region with the sort of images you probably have in mind. I was very much decided to avoid this way of working. At the time I was in close contact with the people of Appleshop in Whitesburg, who were very concerned.

RM: Can you talk about how the book’s title, Moonshine, came about? I’m sort of playing devil’s advocate here, but neither of your books made in parts of Russia - A Hundred Summers, a Hundred Winters and Let’s Sit Down Before We Go - were titled ‘Vodka.’

BVM: I never thought of that! It is true, of course. Moonshine was playing a role in people's life, there was a lot of partying going on. On the contrary, in Russia people drink out of sadness. The title "moonshine" came quite natural to me, it sounds poetic and mysterious, referring to moonshine in general.

RM: When Ron Jude told me about Moonshine a couple of months ago, I was excited to learn that 1) your commitment to this body of work spanned nearly three decades (with visits in 1985, 1987, 1988, 1996, 2007, and 2013) and 2) the notion that MACK was publishing a book specifically about Appalachia. Quite frankly, at first I took issue with the title because of my own filters and imprinting, which is problematic in and of itself, and where the the title of the book took me visually. It wasn’t until I spent some time with the work that it really began resonating with me. I see my own life and family in many of these photographs.

BVM: That is very nice to hear!

RM: Historically, your photographs seem very much about meeting people where they are, even learning their language (as in Russia). There is an unguarded quality in your pictures, which often reveal quiet moments and domestic chaos, often in close proximity of one another, which families tend not to reveal to just anyone, especially those with a camera. Can you talk about your work process?

BVM: Yes, especially the rather closed off communities in the Appalachian mountains! I am lucky to have some social intelligence. I am curious and I like being with people. I always live with the people I photograph, working with small, amateur cameras, trying not to be there so much as a photographer but rather as a friend, who happens to take pictures. People do not see me as threatening and once there is trust, most people like the attention they get from being photographed.

RM: How it has changed over the years? Do you see your work as a collaboration with the people in your pictures?

BVM: I don't think my way of working changed much over the years, for me it works well.

RM: Moonshine is your third book with MACK and your seventh solo book since 1994. How has the bookmaking process changed for you over time?

BVM: Making a book is like giving birth. It is sometimes painful but also a joy. All depends on the publisher. My current collaboration and relationship with Michael Mack is excellent.

RM: How do you work through the process of editing photographs you’ve produced for, in the case of Moonshine, nearly three decades?

BVM: I looked at all the contact-sheets and the artist and designer, Bas Geerts, did the same. Together we made the choice. I need a second eye to protect me from too much subjectivity as i know the people in the pictures so very well.

RM: You worked with Stephen Gill on your last book, Let’s Sit Down Before We Go. What was editing Moonshine like after that experience?

BVM: It went very well. Of course you have to trust the people you work with for one hundred percent.

RM: Can you talk about the importance of time as it relates to your photographs? One of the things I admire most about your work is its unhurried pace in terms of the span of time your projects take on. It would seem this requires a great deal of trust and vulnerability on both the people you’re photographing and you as the photographer.

BVM: I know this is a luxury. I received several grants to be able to work on this project, so I didn't have to worry about being able to survive. I need time to be able to show what I am looking for. I know what I am looking for and I am a perfectionist. I go on as long as I think I am not ready yet and as long as I still like what I am doing. I like to go back to places. I love to see the same people back and to discover this feeling is réciproque (translated mutual). It gives me the suggestion of belonging somewhere, be it temporarily. People feel that and act accordingly. It is a beautiful and serious game.

RM: How has this shaped your growth as an artist and human being over the course of your career?

BVM: This way of living has become a part of me. I have learned to be tolerant and easy.

RM: How has the book been received amongst those in the book?

BVM: I went to bring the book to Mavis in Kentucky. I was concerned about her not being in there that much. Or her children. That didn't seem to brother her that much. I had already written to her that it was not a family album. But the text was giving her difficulties, where I wrote about Junior shooting at her. "He can't defend himself any more," she said, which shows her deep-going solidarity.

Moonshine was printed in an edition of 3,000. In 2015 there will be an exhibition in New York with Yancey Richardson.