Hardcover| 8 x 10 inches | 144 pages | 93 black and white photographs | Temple University Press, 1989 | Builder Levy | $25

Images of Appalachian Coalfields was probably the very first photobook specific to Appalachia I ever bought. In late 2009, I saw Levy's picture of Chattaroy, West Virginia native Nimrod Workman in Coal Country: Rising Up Against Mountaintop Removal Mining, the companion book to the documentary film, and wanted to know more about the photographer who'd photographed in my home town. Chattaroy isn't exactly that widely known (or photographed). An online search about Levy led me to his book, which I ordered right away.

When the book arrived, I sat down and pored over the pages and examined each photograph looking for more pictures from Chattaroy. Then, I noticed several pictures were made at Eastern Coal Company in Stone, Kentucky across the Tug River in Pike County. My pawpaw, Cecil May, was a mine foreman and worked underground for Eastern for over 40 years. I just knew I was going to see him in one of Levy's photographs. Well I didn't see my pawpaw, but I decided to email Levy to thank him for making the work and tell him the story about my connection to Chattaroy and Eastern Coal Company. That email struck up a conversation, which developed into a friendship. Later this month, I'll get to meet Builder Levy for the first time at the 2016 Appalachian Studies Association conference in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, where I'll be part of a panel with Levy and Dr. Sylvia Shurbutt of Shepherd University.

Images of Appalachian Coalfields begins with a powerful combination; a foreword by Cornell Capa, the brother of Robert Capa (yes, that Robert Capa) and an introduction by Dr. Helen Matthews Lewis. The introduction, twenty-two pages long, should be required reading for anyone making work in Appalachia. It's broken out by themes of work, community, and legacy, which sets the structure of how the photographs are presented (in identical sections). Lewis sets up the work with the care and scholarship anyone familiar with her work would expect, ending with, "The current plight of mining communities is strong evidence that the enrichment of the coal producers has resulted in the impoverishment of the region and its people."

The photographs from Levy's first book were made between 1968 and 1982. He started making pictures in Appalachia when he took a 10-day trip to Boone, North Carolina. On his return to New York, he made a detour through Mingo County and stayed with a VISTA worker who introduced him to some local folks. Working slowly over time and returning to the coalfields often, Levy began to build the body of work that would eventually become Images of Appalachian Coalfields.

One of the important things I gleaned from my early conversations with Levy was how important it was to him to give back prints. It's something I started incorporating into my practice because of him. I've given away at least three copies of this book (as well as Rob Amberg's Sodom Laurel Album, which I'll write about later) as examples of the kind of work I want to see more of, that I feel we all need to see more of. This isn't a book any MTV producer referenced as an idea for a new show. Instead, it's a deliberately slow an quiet approach to telling a story with grace and intention.

From the dust jacket: "Levy describes the sometimes mixed reaction he received from miners, foremen, and company guards at various mining sites. By "reading" the images, one senses that he did no simply gain access to witness but fully participated in the daily "mantrips," the comfortable hospitality, the unity of miners surfacing after a long day underground. Images of Appalachian Coalfields forces the reader to confront the life of a mining community, to recognize the faces of struggle, camaraderie, defiance, endurance, and to admire the intense vision of a photographer whose love of subject pays homage to the human spirit."

I've selected some of my favorite spreads from the book and included the caption information.

Spread one, pages 42 and 43. Left: Loaded coal cars in the mines, drawn by animals or men years ago, are now moved or "hauled" by motorized vehicles called "motors." (One of Eastern Associated Coal Corporation's mines; Boone County, West Virginia, 1982) Right: Several years after he was photographed, Andrea Kosto was killed by a large piece of slate that fell as he was trying to locate an obstruction under the loading tipple. (Sycamore Mining Company; Cinderella, West Virginia, 1971)

Spread two, pages 50 and 51. Left: Workers emerge form the mine at shift's end. (Wolf Creek Colliery; Lovely, Kentucky, 1971) Right: Since the late nineteenth century, Black miners have been among the leaders in the struggle to defend and expand the rights of all coal miners. (Old House Branch Mine, Eastern Coal Company; Pike County, Kentucky, 1970) [Editor's note: although not originally identified in Images of Appalachian Coalfields, the miner's name is Toby Moore. He appears on the cover of Levy's third book, Appalachia USA.]

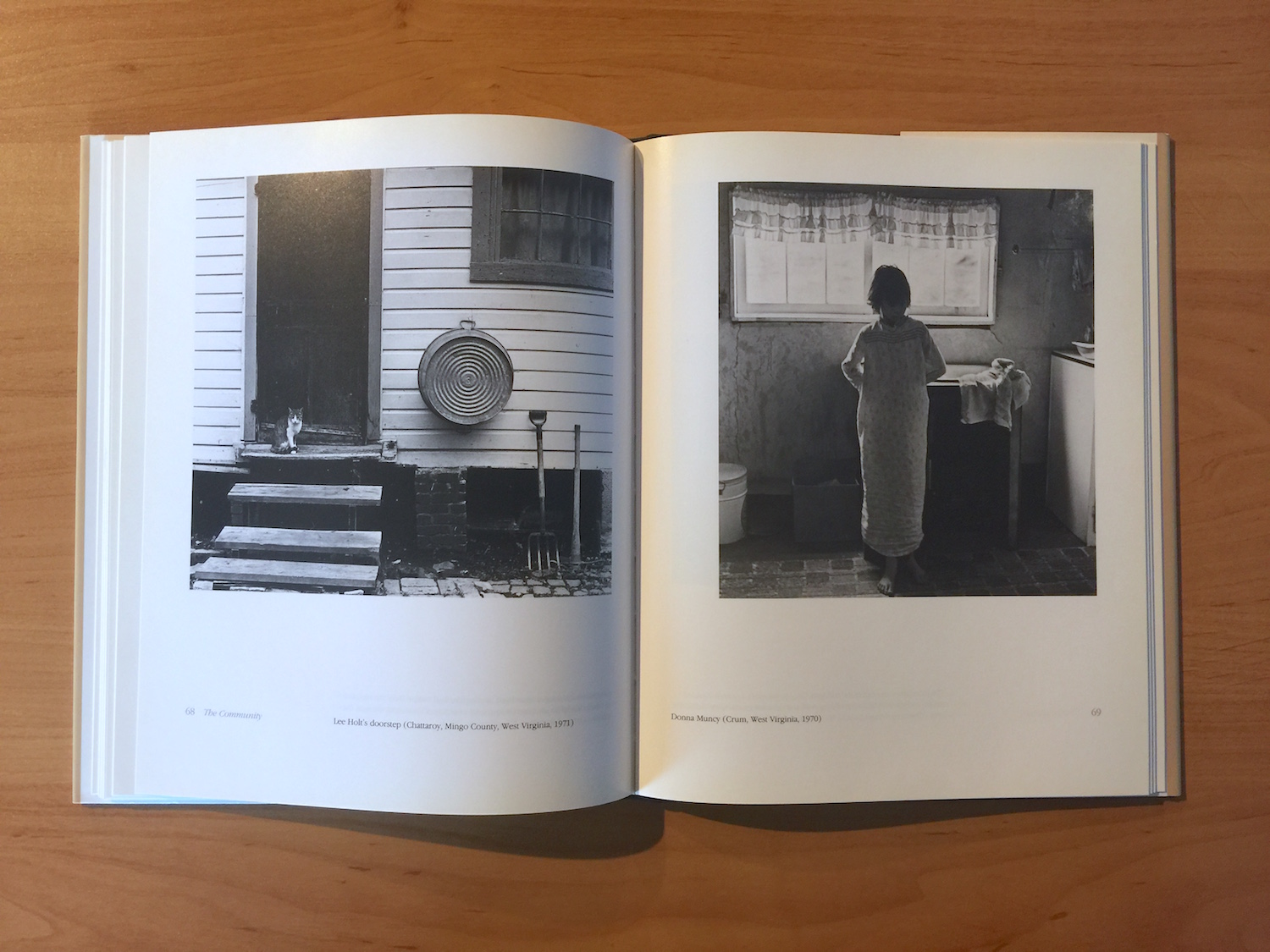

Spread three, pages 68 and 69. Left: Lee Holt's doorstep. (Chattaroy, Mingo County, West Virginia, 1971) Right: Donna Muncy. (Crum, West Virginia, 1970)

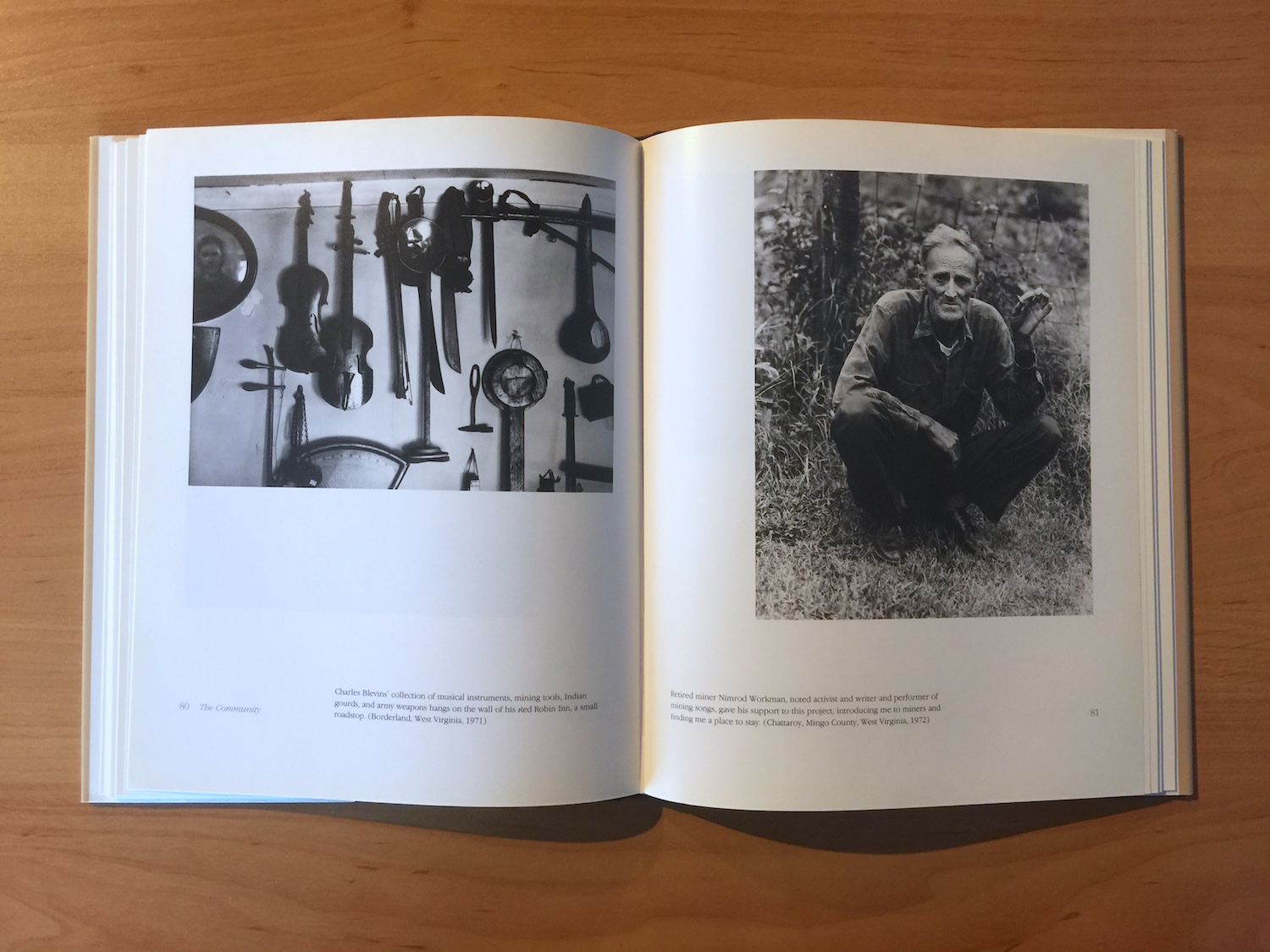

Spread four, pages 80 and 81. Left: Charles Blevins' collection of musical instruments, mining tools, Indian gourds, and army weapons hangs on the wall of his Red Robin Inn, a small roadstop. (Borderland, West Virginia, 1971) Right: Retied miner Nimrod Workman, noted activist and writer and performer of mining songs, gave his support to this project, introducing me to miners and finding me a place to stay. (Chattaroy, Mingo County, West Virginia, 1972)

Spread five, pages 110 and 111. Left: View from Highsplint bridge. (Harlan County, Kentucky, 1974). Right: Williamson, "Home of the Billion Dollar Coalfields." (Mingo County, West Virginia, 1972)

Long out of print, you can pick up a used copy of Images of Appalachian Coalfields relatively inexpensively online from a number of sites. I highly recommend this book.