[Left: my father-in-law, Wayne Justice on a walk on the family property the morning after Christmas. Elgood, West Virginia (Mercer County). Right: the Justice family woodshed. Both photos were made 26 December 2015.]

I'm old enough to remember Polaroid film when it was still as readily available as SD cards are today. Even as a kid, there was something special about the smell of pack film, the pitched whine of the camera as it pushed out the picture, and the wait for the image to appear. I've been spending time with some of the photos from my childhood thanks to my Mom and my aunt Rhonda who have loaned me several family photo albums (also now a thing of the past as most of our photos live on our devices or online). Talk about nostalgia.

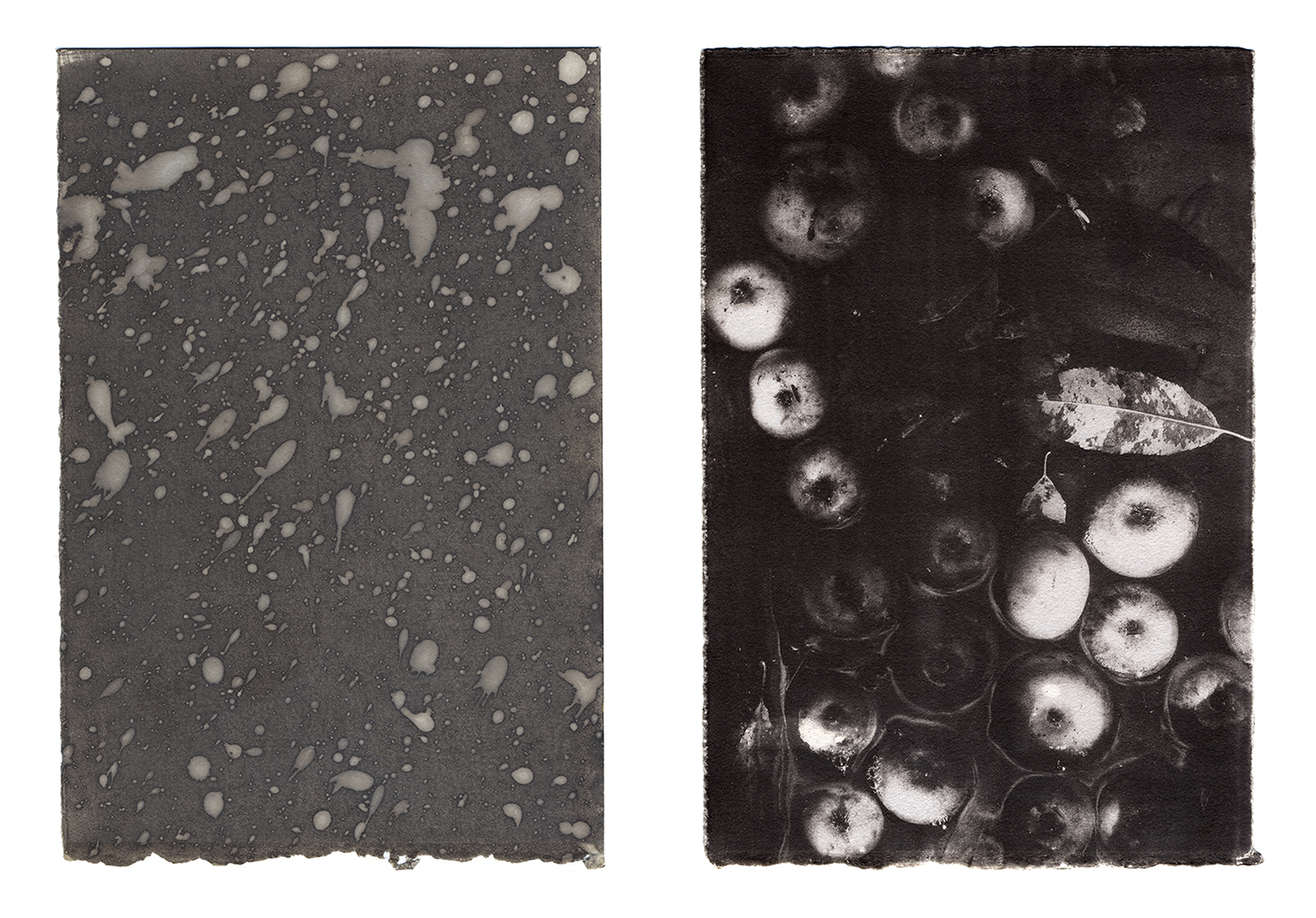

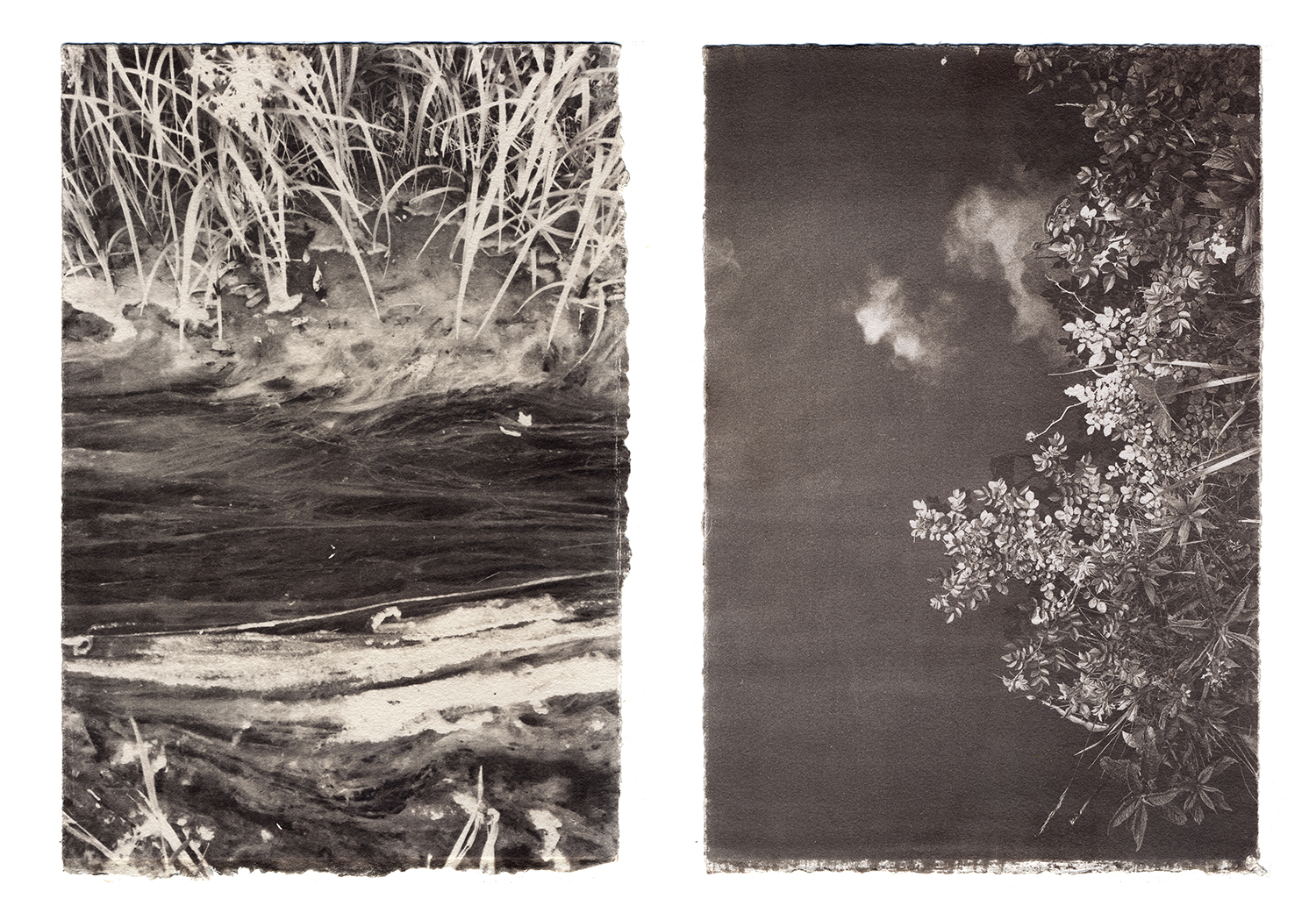

A couple of years ago, my good friend Nic Persinger reintroduced me to instant film. Around that same time, I'd picked up a Fujifilm Instax 210, which was a little more similar to the Polaroid cameras I grew up with. Nic suggested I try a Land Camera, one of Polaroid's most popular series. He sent me one to try out (a 1969 model, which you can pick up for about $3) and I've never looked back. The camera shoots pack film, which is still made by Fujifilm, and comes in color (FP-100C) or black and white (FP-3000B), and produces a 3.25" x 4.25" (approximately) print. Film runs about $10 for a box of color film and $25 for black and white. This isn't a how-to article, but rather one that will share my love for these cameras and this film. I also wanted to share some of my favorite pictures I've made with this combination over the last couple of years and a little bit about what I do with these pictures. (These were scanned on an Epson V600 flatbed scanner.)

[Row one, left to right: Ed Shepard, Welch, West Virginia; Doug Dudley, Mingo County, West Virginia; Downtown Williamson, West Virginia; and Baisden, West Virginia. Row two, left to right: Curtis Meade, Red Jacket, West Virginia; Walmart, Kimball, West Virginia; Grant's Supermarket, Princeton, West Virginia; and Baisden, West Virginia.]

I carry my Polaroid in my camera bag whenever I'm in the field. Cumbersome as it is, it's almost always with me. I can say that I've probably given away as many of these pictures as I've kept. I've found them to be wonderful leave-behinds, small mementoes to thank folks when I make their portrait with either my digital or film cameras. If you've never seen the look on a kid's face when they see a Polaroid for the first time, you're missing out. Most adults are still giddy to get a one of a kind print handed to them. There's a real magic to it.

[Row one, left to right: Abandoned church near St. Matthews, South Carolina; Donny Brook Road, Raleigh, North Carolina; Sugar Grove, Virginia; and Bluefield, West Virginia. Row two, left to right: Monongah, West Virginia; Jefferson Davis Highway, Virginia; Cary, North Carolina; and Harlan County, Kentucky.]

Instant film has made a comeback in the last few years. In fact, PDN just reported that Fujifilm's Instax film was the bestselling item in Amazon's camera department over the holidays. There's something about holding a picture you've made. And there's something to giving them away. With so much digital content pushed today, it's a real pleasure to hold an actual photograph. Each picture is unique in and of itself, a true one of a kind. I love that about this process. The pictures are imperfect - beautifully imperfect and individual.

Here are some technical notes about the camera I use. Again, this isn't a how-to article, but I wanted to share some basics.

I have a model 340 Polaroid Land Camera, which I've customized with the state of West Virginia on the camera's cover. At the far right, you can see the modifications Nic made so that the camera now takes three AAA batteries instead of the native 4.5 volt battery. Often with these cameras, batteries have been left inside for decades and have corroded. There are tons of how-to articles and videos on how to modify Land Cameras, which I'll leave up to you to find. As far as battery usage goes, I can say that I've shot hundreds of exposures without changing the batteries a single time.

These cameras are beautifully simple and straightforward. At left, you can see the view window and the focus window. This is a rangefinder, so you compose your image in the view window and use the rangefinder pushbutton to focus (1). When your image is in focus, cock the shutter (3) and press the shutter release (2). That's it. You pull the white numbered tab (which is numbered 4) and you have your print. I usually wait two-three minutes before peeling apart the print and negative. (Note: I've recently peeling my prints away in a manner that leaves the black border - as seen in the first two images at the top. I just like the aesthetic of the border it leaves behind.) Once the prints have completely dried, I store them in archival sleeves by Gaylord Archival. There is also a process by which you can scan the negative, but I haven't tried it. Here's a link to the manual for the Polaroid 340 Land Camera.

Earlier this year, I thought it would be fun to share work with folks and have access to film at the same time. I thought I'd run out of film, then a box slid from underneath my seat. I had an idea which goes like this: If you'd like a Polaroid (Fuji) print, send me a box of film and specify the number you'd like me to send you (just one, selected from 1-10) and when I've made the picture, I'll drop it in the mail to you. If you'd prefer a picture from my archive, that works too. Some local camera shops carry this film. I've also ordered it from B&H or Amazon.

Please limit your selection to one per box of film you send. And holler if you have any questions. Here's to more film and more heartwork in 2016. Thanks!