On Monday, March 23, in McDowell County, West Virginia, photographer Marisha Camp and her brother Jesse found themselves confronted by an angry and hostile group of folks, who accused them of taking photographs of children without permission. The Camps, who were on the road gathering material for a television show they hope to pitch later this year, were detained and threatened with physical violence by these local citizens. After a 45-minute confrontation, the Camps were escorted out of the county by the West Virginia state police.

The story was picked up by local news stations and by national photography magazines and blogs. As is usual when Appalachia is the subject, the story was told primarily by and about one group—outsiders visiting the area. That’s not to say the Camps’s accounts of what happened aren’t valid, but they’ve been given a platform not afforded many of the others involved. The locals have been portrayed as vigilantes, as mob- or gang-like. One national photography magazine titled their story, “West Virginia Mob Reportedly Detains Photographers for Looking Out-of-Town.” Let’s be clear: the Camps weren’t detained for looking “out-of-town.” They were detained, illegally this West Virginian and photographer believes, because parents thought they'd photographed their children without their permission.

Knowing that I am from West Virginia and that I have a professional and personal interest in work being made in and about Appalachia, a friend posted the news story on my Facebook wall. Several other people contacted me to ask what I thought about the situation. After watching the local news story, I knew there was much more to the story. I knew there would be fallout, and feared that locals would bear the brunt of it.

Searching for a greater understanding of the incident and the actions that caused it, I began reaching out to those directly involved. I contacted Marisha Camp on Thursday, March 26, and over the next few days I exchanged calls and dozens of text messages with her and her brother. On April 2, I spoke with Jennifer Adkins, the woman who accused the Camps of photographing her children and threatened them with a gun.

I also contacted journalists and filmmakers who have worked in Appalachia, and a local photographer, to gain as much perspective as possible about what happened that day. I asked them to comment on the situation in McDowell County because none of the reporting thus far attempts to look at the long history of misrepresentation in Appalachia. Sure, this could’ve happened anywhere. But it didn’t. It happened in McDowell County, West Virginia. And although the Camps may not have been intentionally seeking out “poverty porn,” many local residents view photographers, both insiders and outsiders, with understandable suspicion.

“You don’t look like upstanding citizens.”

The Camps had been on the road for months, working their way across the country filming and making photographs. On Sunday, March 22, they filmed a church service in McDowell County. The following day, they decided to collect B-roll footage. “We noticed these three obese kids playing with sticks in [a] driveway,” Jesse Camp recalls. “When we drove by I asked them if they were having a stick fight. They sort of laughed and that was that. We drove on.” On their way from Jolo to Raysal, the Camps parked their Volvo station wagon with Massachusetts license plates at a gas station and crossed the road to photograph some houses and talk with some folks. Soon thereafter, Marisha Camp heard someone yelling across the road and noticed a van blocking in their vehicle. The van’s owner, Jennifer Adkins, was upset because she thought the Camps were photographing her children without her consent, and she demanded the pair hand their cameras over. The situation escalated quickly.

According to Marisha Camp, Adkins immediately threatened them. She opened the door of her van and pointed to what she said was a gun, stating that the Camps weren’t leaving until they handed over their cameras and the police arrived. Afraid and panicking, Camp tried to call for help, but had no cell service. Camp was able to record audio of the incident on her phone. “Have you all looked at yourselves in the mirror? You don’t look like upstanding citizens,” Adkins can be heard saying on the recording. For nearly 45 minutes, the situation intensified. An angry crowd grew around the Camps, despite Marisha Camp showing Adkins’s husband the images on one of their cameras in an attempt to prove that none of the images were of their children.

Local parents were already on edge due to the disappearance of a young child in the area: The same day the Camps were filming the church service in Jolo, less than a hundred miles away in Pulaski County, Virginia, five year-old Noah Thomas went missing. The sheriff’s department received more than a hundred tips, many of which identified suspicious vehicles in the area. (Sadly, Thomas’s body was found on his parents’ property in a septic tank Thursday, March 26, five days after he was reported missing. His parents have been charged with felony abuse and neglect.)

Finally, West Virginia state police arrived on the scene. After assessing the situation, they escorted the Camps out of the area and lectured them about how they “ought to be careful about not making ugly pictures about the people of West Virginia,” Marisha Camp says. Later that day, she contacted the McDowell County sheriff’s department and was told by a deputy, “You’re lucky you weren’t shot.”

“We love West Virginia.”

“I’m a gypsy, self-admittedly,” Jesse Camp told me on the phone on March 31. “I love traveling every nook and cranny of America. My sister and I have been road tripping forever, man. We’ve been everywhere, all over the South, and 99 percent of the people we meet are cool.”

Jesse Camp says he and his sister had been all over West Virginia. “Logan, Omar, Iaeger, War, Jolo and Bradshaw. You know man, West Virginia is like the most outlaw place. We love West Virginia.”

Marisha Camp echoes her brother, and she’s been actively responding via Facebook to inaccurate claims from McDowell County residents about the incident. “We really love West Virginia, and it was utterly heartbreaking to think about not going back,” she says. “I know not everyone [there] is like that.”

Also upset by the behavior of the police, Marisha Camp wrote a letter to West Virginia Attorney General Patrick Morrisey, detailing the events. In the letter she writes that she “strongly believes” in combatting “negative stereotypes of the region,” but calls the actions of the police “absurd and about as counterproductive as it gets.”

“It is for everyone's benefit that incidents like this are taken seriously,” she writes. “I would have been encouraged to press charges anywhere else rather than be run of town like a ‘long haired hippie’ and then told by law enforcement that I'm somehow lucky because I wasn't murdered.”

Despite all this, the Camps say they’ve received overwhelming support from residents of McDowell County. Many have contacted the Camps via Facebook apologizing for the actions of a few people and offering them places to stay if they make it back.

“We had no choice but to question their motives.”

Jennifer Adkins was on the phone with a neighbor when her 13-year-old son walked in the front door and told her, “there was a guy out there taking pictures.”

Adkins hung up the phone and immediately called 911 to report the incident. She, her husband and their two sons got in their minivan and drove after the Camps in order to get a license plate number. (As a parent, I understand the fear and concern Adkins must have felt for her children in the moment, especially considering the missing child in the news.) Once they found the Camps's vehicle at a gas station in English, they called 911 again to report the tag information.

“I was floored by their appearance. They looked like bums. I don’t mean that to sound derogatory, but they did,” Adkins told me. “I saw [Marisha Camp] put one of her cameras away and then she started showing my husband pictures from the other one.”

Both Jesse and Marisha Camp deny making photographs of the Adkins’s children. But the family didn’t know what the Camps were up to because they never came to their door to ask if it was OK to talk to their children or photograph them. Therein lies the problem for me, and for Adkins. “I can understand them [the Camps] being scared, but we had no choice but to question their motives,” Adkins says. “I wouldn’t have ever given them permission to take pictures of my kids, let alone talk to them, but they never gave me the chance.”

Adkins admits she threatened the Camps. “I mean, I said I had a gun, but I didn’t. I wanted them to know I meant business and that they weren’t leaving until the police showed up. I told [Marisha Camp] that she could leave by ambulance or by a police car, but she wasn’t going nowhere until I saw that she didn’t have pictures of my boys,” Adkins recalls. Soon thereafter, Adkins says, residents she didn’t even know began to gather around. She says the other residents, who must’ve felt they were looking out for their own, "sort of took over."

I asked Adkins about judging the Camps by how they looked when for so long West Virginia has been the butt of so many jokes about appearance. I had a really hard time with this one. “I know,” Adkins says, “but if I go to New York City, I’m going to stand out and possibly be stereotyped. Anybody who knows me knows that I’m outspoken. We [West Virginians] always get portrayed bad. And we didn’t know what they were up to.”

A few days after the confrontation, Adkins was interviewed by WVVA, the local news station, after they saw her Facebook posts about the incident. Adkins has taken down most of the posts, but I had taken screenshots for my notes. In one post, she wrote, “They are from Mass. and said they were doing a ‘documentary’…. All I can say is they best NOT COME BACK TO RAYSAL!!!!!” Someone commenting on Adkins’s Facebook page posted the Camps’s license plate number, and several commenters also included pictures of the Camps’s vehicle.

“We don’t get to choose who makes work in Appalachia.”

Elaine McMillion Sheldon, a native West Virginian, spent more than three years on and off working on Hollow, an interactive, community-driven documentary project about McDowell County’s past, present and future from the perspectives of local residents. When I reached out to her, she was beside herself about the incident and didn't understand why residents would react as they did. “What is the goal here? I think it's a question of how we want to be seen,” she says. “Do we want to be seen as a threat?”

Sheldon says residents she talked to in the County are divided about the incident. She was surprised that local photographers told her they don’t agree with the kind of work the Camps were making. Sheldon says: "We don’t get to choose who makes work in Appalachia. We can’t police who makes pictures here, but we should try to educate those who want to come in to document, and encourage a more nuanced story. We all need to stand together as artists, regardless of whether we like a specific artist’s work or not. You can't pick and choose whose rights you support based upon whether you like or dislike their work. All artists have the same legal rights, regardless of the art they create."

“The visual equivalent of hate speech.”

Kate Fowler has worked in West Virginia extensively and was recently hired by the Magnum Foundation in New York. Her film, Nitro, chronicles the complicated relationship between a small West Virginia town and the chemical plants that both provide jobs and impact the environment in West Virginia’s “Chemical Valley.” Fowler also spent a great deal of time in McDowell County working on her film With Signs Following, about the late Mack Wolford, a preacher and serpent-handler from southern West Virginia.

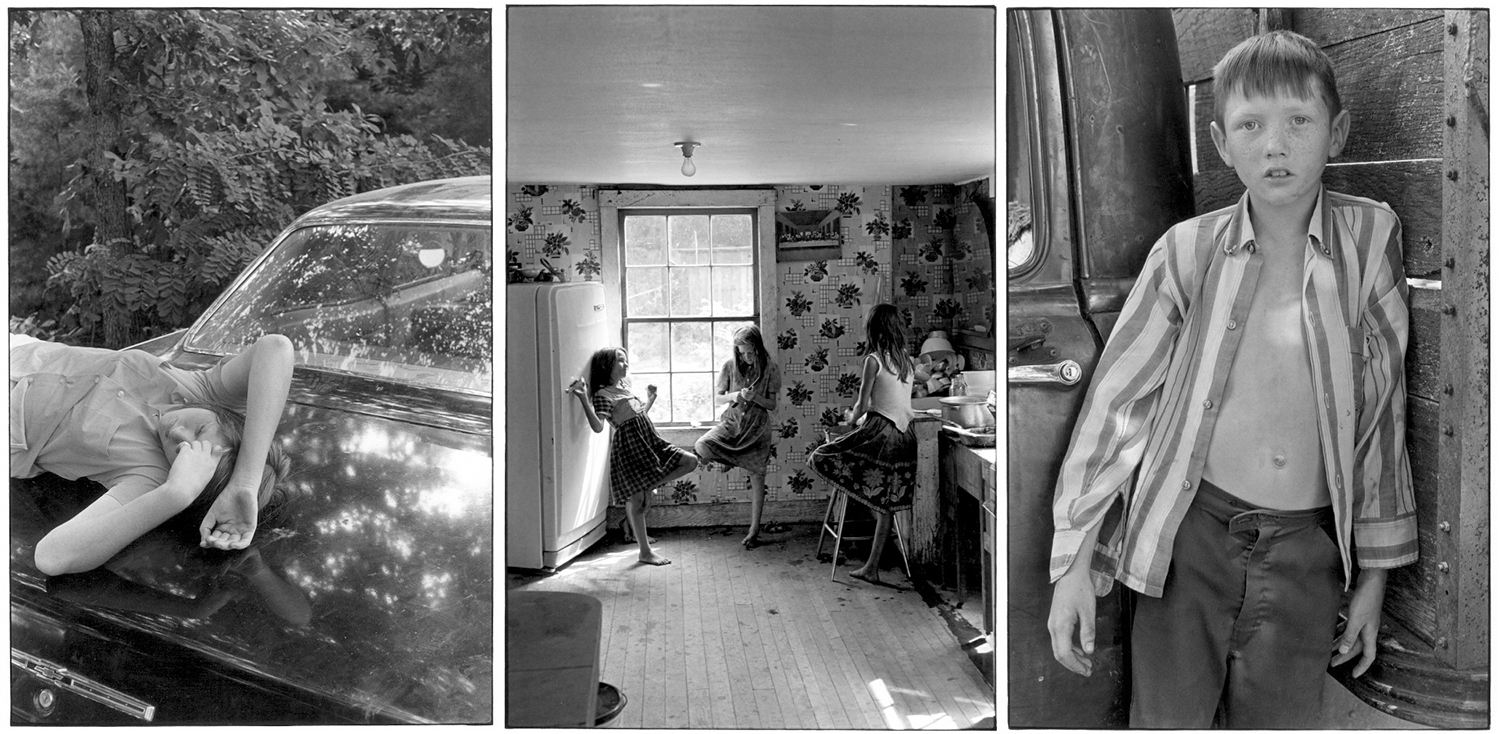

Fowler views the actions of the Camps and the reactions of the local citizens as part of a long, complicated history of photography in Appalachia.

Many in West Virginia, Fowler says, recognize that outsiders who’ve photographed their communities without consent have participated in the “dissemination of classist and bigoted rhetoric—the visual equivalent of hate speech.” Fowler also points out that when a small group of citizens decided to speak up for themselves, “the Internet...mobilized to discredit and to once again, deny the subject’s capacity for critical engagement.”

“No person deserves to be threatened with violence” or held against their will, Fowler adds. But, she says, “We [as photographers] must not presume that our intentions are clear, nor deny the trauma we may invoke through our actions, tools or intentions.”

“Am I supposed to go and knock on each and every door?”

Alan Johnston is a native and lifelong resident of McDowell County, West Virginia. He’s a musician and landscape photographer I met several years ago through Sheldon’s Hollow project. I reached out to him to get a local photographer’s perspective on what happened and he was kind enough to talk with me.

Johnston says he was “genuinely concerned” when he heard about the incident, especially when he considers what it might mean for his ability to work locally. “I really don’t understand what I’m supposed to do,” he says. “Do I tell somebody at the mouth of the holler that I’m taking pictures of barns and landscapes? How will the people in the head of the holler know what I’m doing? Am I supposed to go and knock on each and every door and report to people who I am and what I’m doing?” He notes that he rarely photographs people he doesn’t know, but rather photographs landscapes of McDowell County for his own pleasure.

Johnston recalled a time a few years back when he was out making pictures in the county and pulled off on the side of the road to photograph a horse in a barn. “All of a sudden this woman came out on her porch and started yelling at me. ‘You better not take any bad pictures on this mountain,’ she yelled.”

He staunchly defends his right to make pictures on public property, but confided that there are a whole lot of people “skeptical of anyone doing anything around here.” So it’s clearly not just outsiders that are met with suspicion.

Cultural insensitivity and privilege

Jesse Camp says this could’ve happened anywhere. It’s true. It could’ve. But it didn’t. It happened in West Virginia. And if you’re not familiar with the long history of visual misrepresentation of the region, then close your eyes and think about the first thing that pops in your head when you hear the words “West Virginia.” See what I mean?

Understanding the very real history of misrepresentation in Appalachia—particularly McDowell County, West Virginia, which is often portrayed as a hopeless pocket of rural Appalachia (a depiction I take great issue with)—by no means implies that it’s justifiable to hold people against their will and threaten physical violence. It’s also unreasonable to judge anyone by his or her appearance or how they talk, no matter who they are or where they’re from. But it’s important, although not easy for everyone, to understand where the anger comes from. It’s only through self-awareness that both photographers and local residents can hope to prevent incidents like this.

West Virginia is in my DNA. It’s a huge part of who I am. I’m also a photographer, which is an equally huge part of who I am. Often when these two meet it can be a challenge to find a balance, to reconcile history with the present, to challenge what we’ve been shown with what we know. I’m all too aware of how we’re portrayed, joked about and stereotyped. I’m also aware of how important listening is, and how making work in Appalachia isn’t as much about me as it is about honoring, respecting and searching for home. I’m not saying the way I work is the right way, if there is such a thing, but I am saying I don’t want to be another taker in a long line of takers.

Without a true understanding of the long history of takers in Appalachia, it can be hard to understand why locals reacted the way they did. The Camps deny both their privilege and a lack of understanding. They stated to me several times that they’ve been living out of their car, wearing the same clothes over and over again, and doing so with little to no money. But there’s nothing that pisses underprivileged people off more than privileged folks blind to their own privilege. Does that make the Camps bad people? I don’t think so. Does being threatened, blocked in, called names, yelled at and held hostage until state police arrived seem warranted? Again, I don’t think so. The Camps are likable people and I’ve found nothing in the time I’ve spent communicating with them that would lead me to feel otherwise, but I can raise concern over their cultural insensitivity.

Does that mean they can’t make work in Appalachia? Absolutely not.

Privilege can be tricky. I know this all too well. But photographers should be aware of it and sensitive to it. Marisha Camp was quick to counter my mention of this via text. “I’ll bet that lady [Jennifer Adkins] makes more money than me.”

This isn’t a situation in which it’s easy to either support the photographers or support the community. It’s much more complex than that. What would’ve happened if the Camps had knocked on the door of the Adkins house? What would’ve happened if Jennifer Adkins had simply left after seeing no pictures of her children had been taken? If the Camps were more apologetic and disarming in their responses, would the situation have escalated?

This isn’t just a place in a road trip documentary. This place is my home. It’s true that we can’t police who does and doesn’t make work in Appalachia. But when I reflect on this situation, I’m reminded of a saying by my granddad, “Enough is enough and too much is nasty.”

Thanks to Marisha Camp, Jesse Camp, Jennifer Adkins, Elaine McMillion Sheldon, Kate Fowler, Joy Salyers and Alan Johnston for their time in contributing to this article.

(This article first appeared in PDN on 21 April 2015. A condensed version appeared in the July 2015 print issue of PDN.)

©Roger May, 2015. All rights reserved.