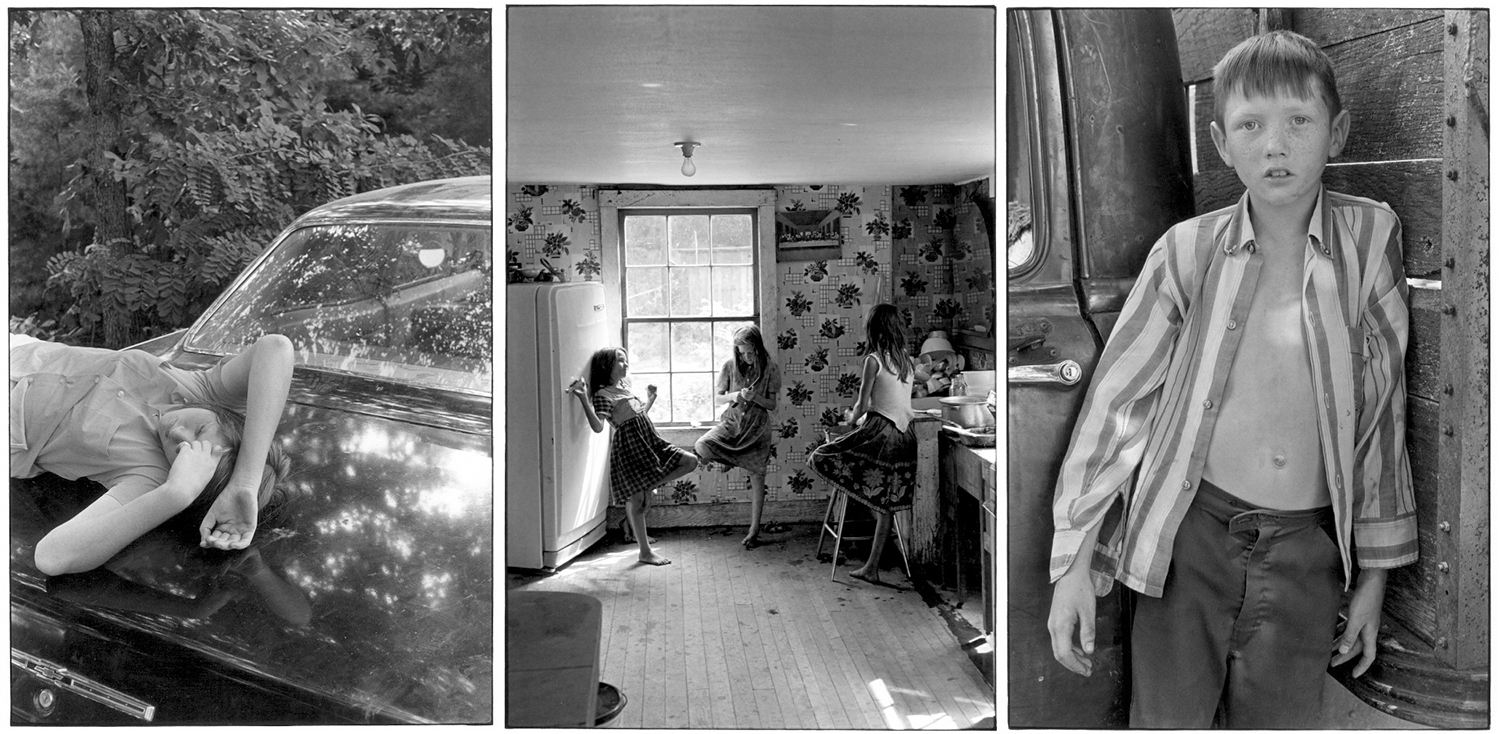

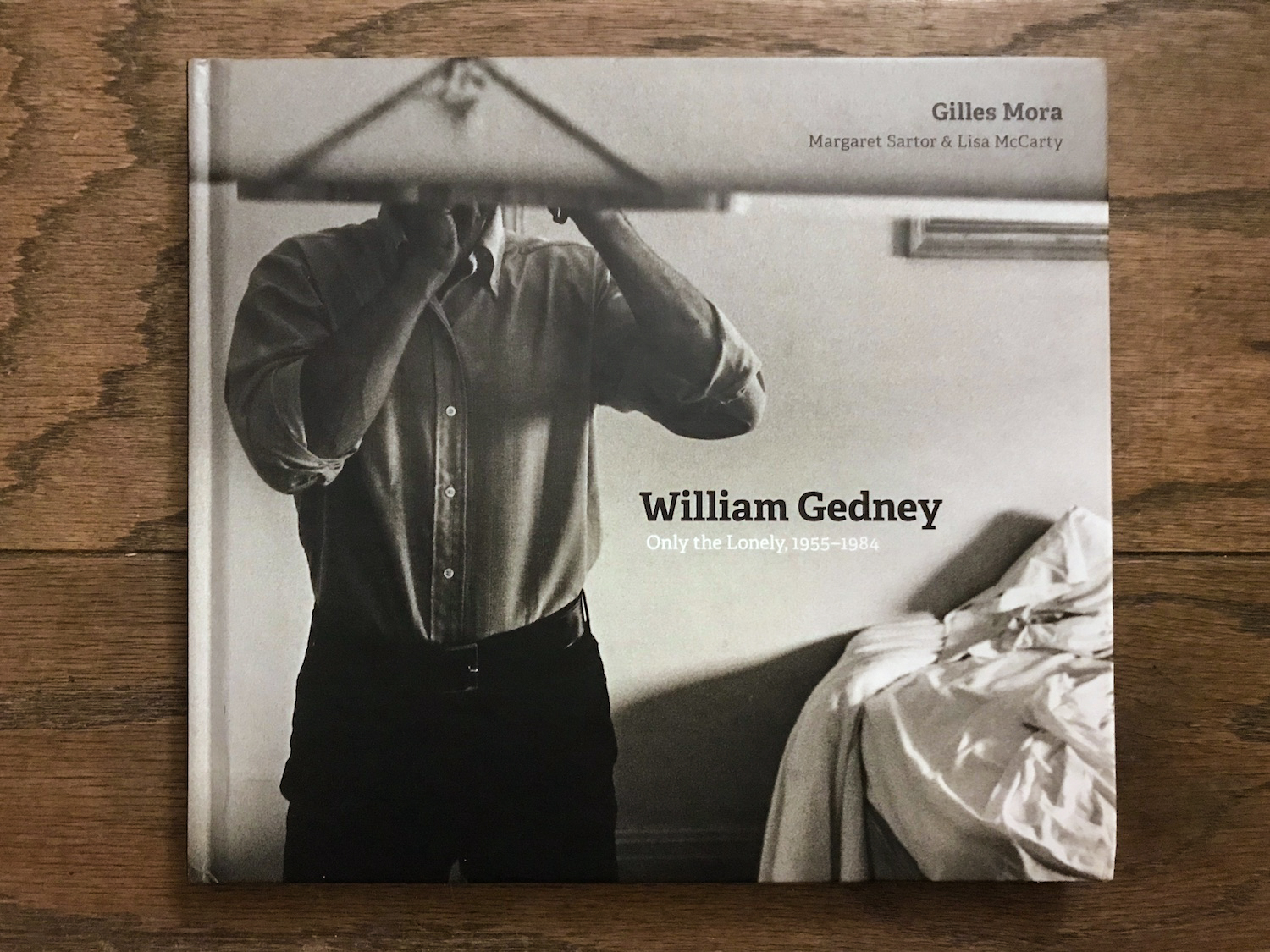

Hardcover | 10.5 x 9.5 inches | 160 pages | 160 duotone photographs | University of Texas Press, 2017 | Edited by Gilles Mora, Margaret Sartor, and Lisa McCarty

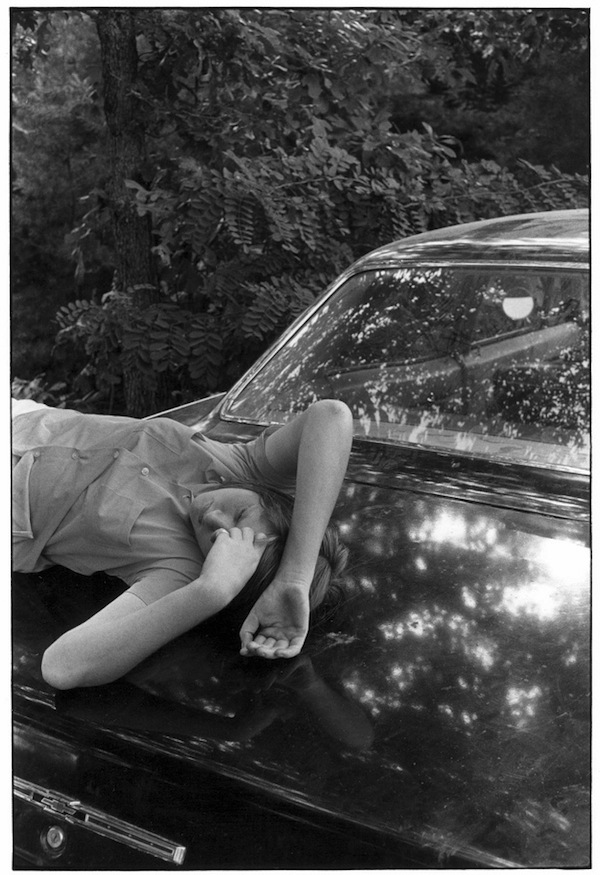

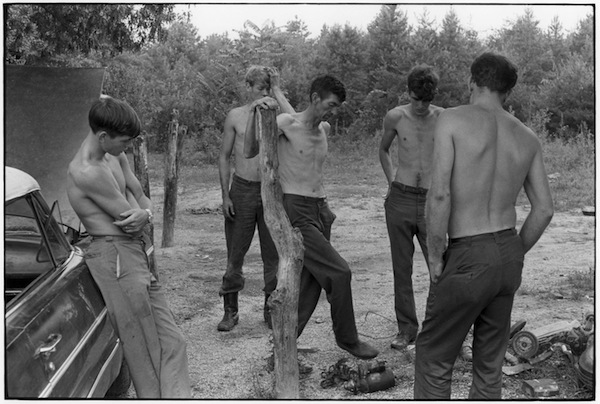

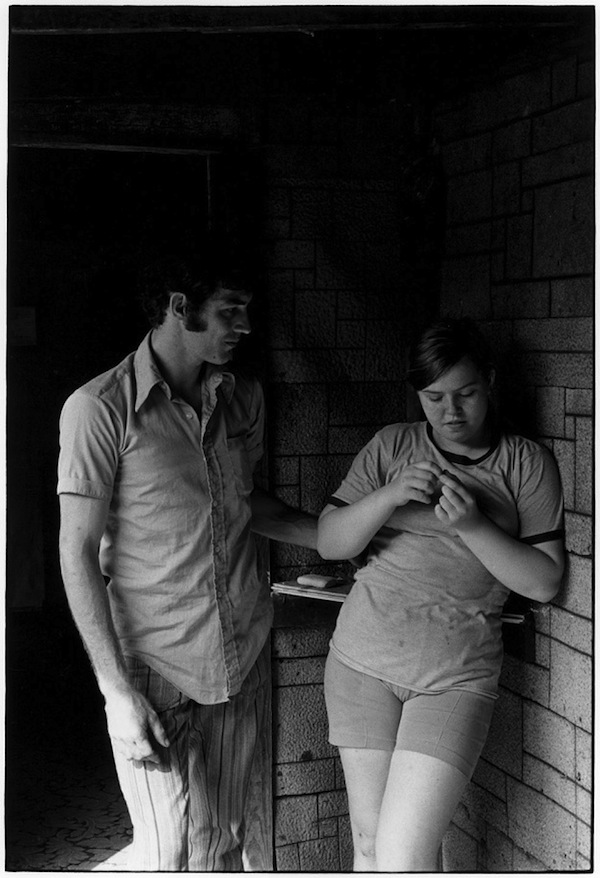

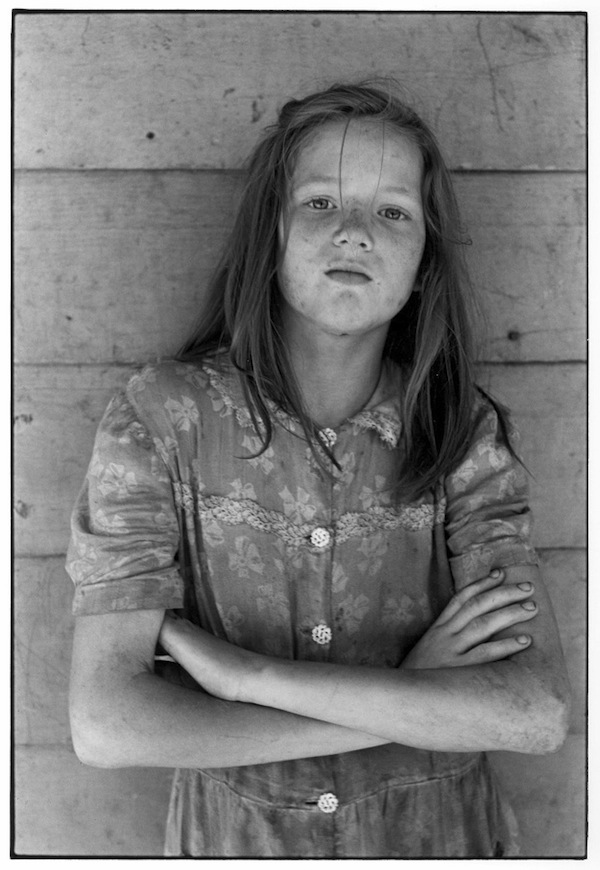

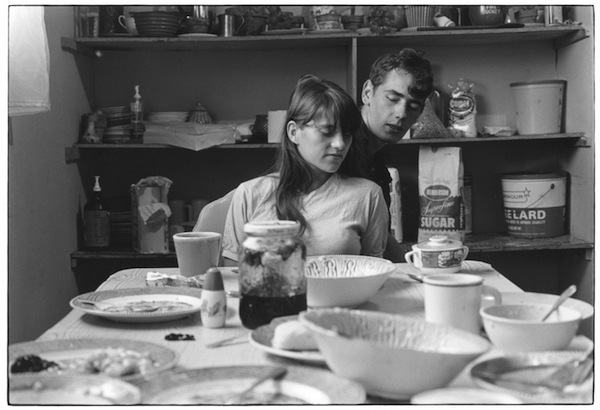

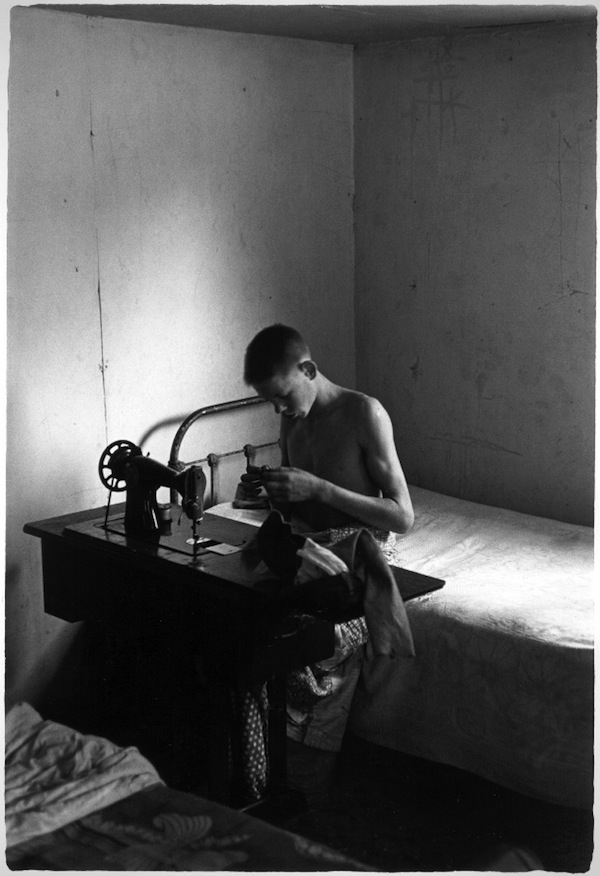

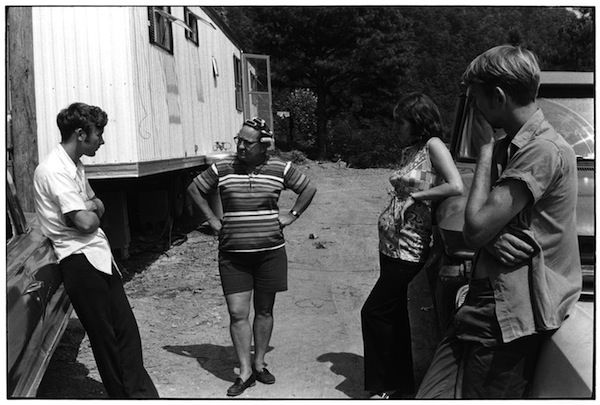

William Gedney’s work was once described as quiet poetry. I can’t think of a finer description of the photographer I’ve never met, but whose work has had a profound impact on my development as a photographer and understanding of photography in all its imperfections and limitations. Intimate is another word often used to describe his work, and although it truly is intimate, I worry that it has become something of a softball descriptor of work that is deeply complex and difficult to categorize. Only the Lonely provides us with a deeper dive into the expansive work of William Gedney. There are three distinct pieces of writing by the editors: “William Gedney, So Similar, So Different: Alone are the Lonely” (Gilles Mora), “Short Distances and Definite Places” (Margaret Sartor), and “Intimate Gestures: Handmade Books by William Gedney” (Lisa McCarty). The book is divided into eight sections of photographs: The Farm, 1955-1959, Brooklyn, 1955-1979, Kentucky, 1964, 1972, United States, 1964-1972, San Francisco, 1965-1967, India, 1969-1971 and 1980, Europe, 1974, and Gay Pride Parades, 1975-1983.

Only the Lonely, is the most recent significant work of this little known photographer. After his death in 1989, Gedney left the responsibility of his archive to Lee Friedlander, who has published dozens of books of his own work and is still actively making books, yet Gedney never lived to see his work in book form. Sean O’Hagan, who writes about photography for the Guardian, called Gedney a “pioneer of immersive documentary.” There has been somewhat of a resurgence in the work of William Gedney, for which I’m incredibly thankful. In 2013, photographer Alec Soth published Iris Garden, a beautiful book of Gedney’s pictures combined with the writing of John Cage (now out of print). Before that, only one other book had been published dedicated solely to the work of William Gedney. In 1993, Duke University became the repository for 51.3 linear feet of Gedney’s work. Margaret Sartor, a photographer, writer, and teacher at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke, was approached by the library and asked to put together an exhibit of Gedney’s work. In 2000, Sartor and Geoff Dyer coedited What Was True: The Photographs and Notebooks of William Gedney (which quickly sold out and is also out of print).

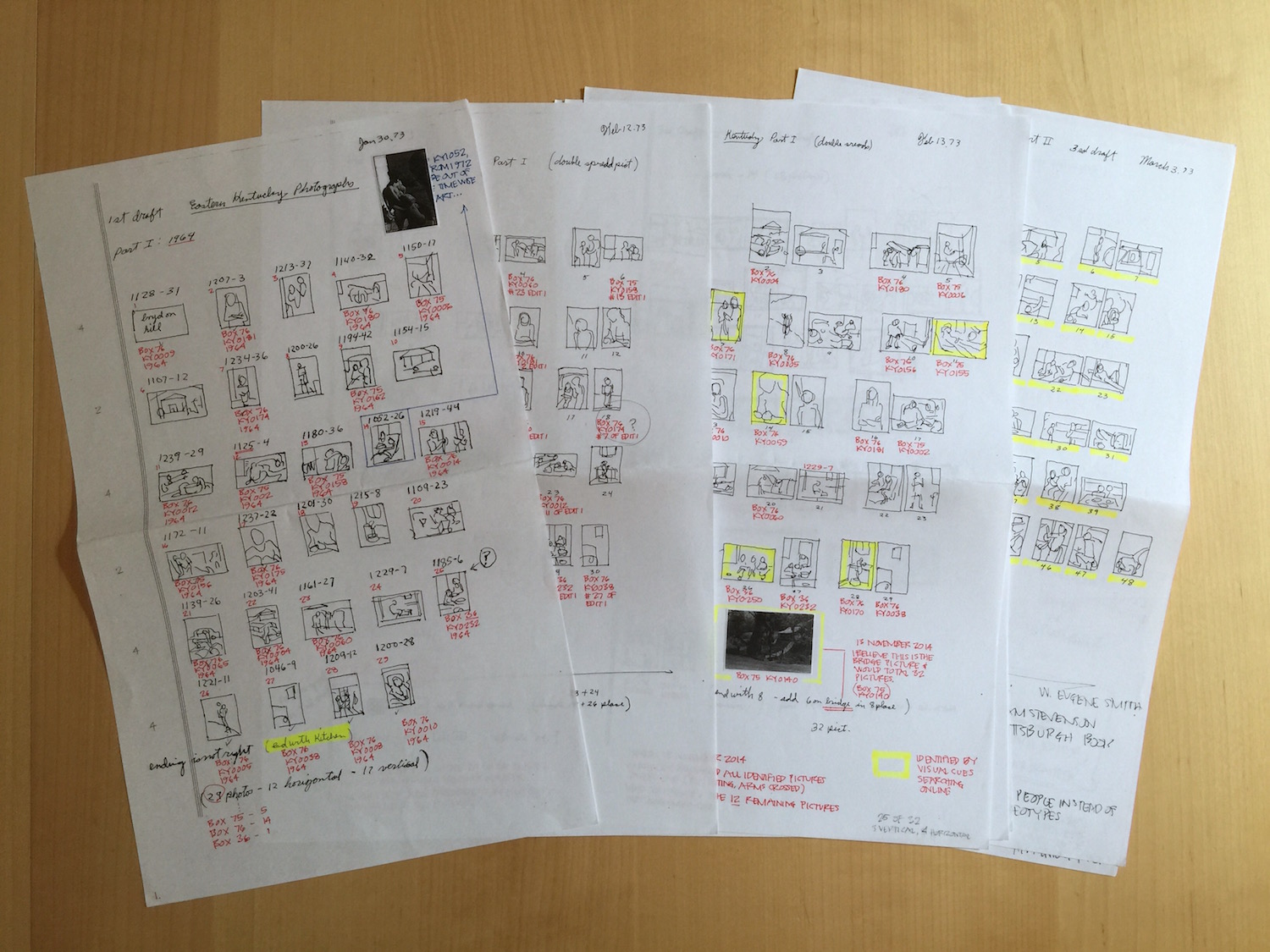

William Gayle Gedney died on June 23, 1989 at the age 56. In his lifetime, he was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship for photography (1966-67), a Fulbright Fellowship for photography in India (1969-71), a National Endowment for the Arts grant in photography (1975-76), and several other grants and fellowships. He had a show at the New York Museum of Modern Art (1968-69) as well as more than a dozen other exhibitions. I wrote about my desire for seeing Gedney’s Kentucky work come to fruition in book form exactly as he intended here.

In her essay “Short Distances and Definite Places,” Sartor writes of Gedney, “People trusted him. Moreover they trusted how he saw them.” This gets at the very heart of documentary and place-based work for me. It isn't enough to just earn the trust of folks who let you into their lives, although it is a critical and foundational step. Would that all of us in our documentary practice earn the trust of people to the extent that they trust how we see them. What a beautiful relationship to strive for and what a beautiful book to have as a reminder of its possibility.